| Name | K4 Kiosk No. 4 |

| Date | Introduced in 1927 |

| Manufacturer | BPO |

| Usage | Public call box |

| Further notes |

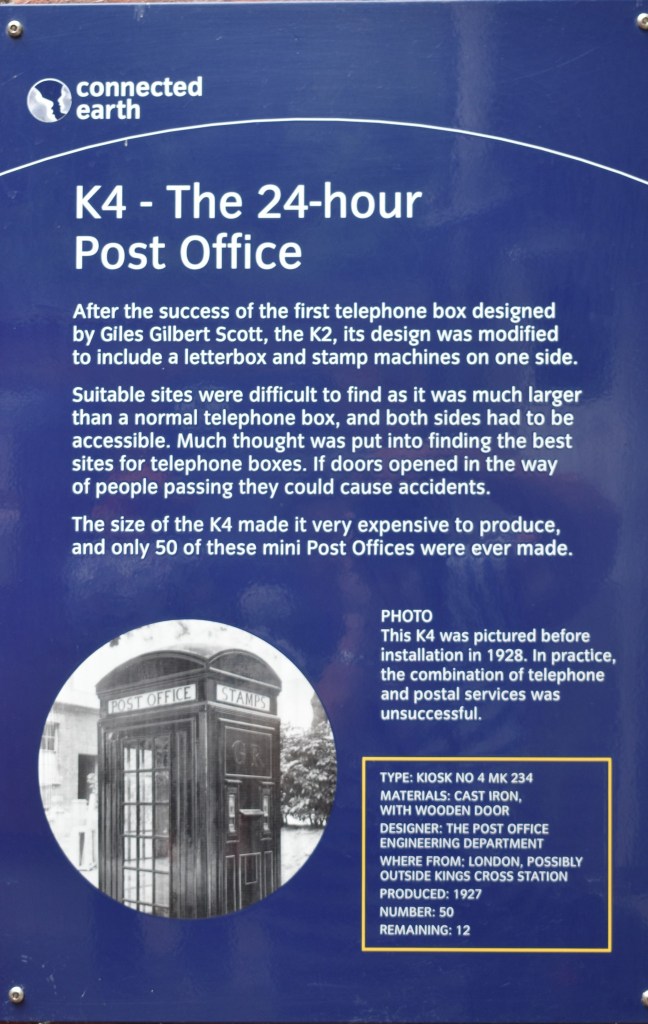

| Kiosk No. 4 [Introduced in 1927] Kiosk No. 4, introduced in 1927, was a rare and experimental British telephone box developed by the Post Office Engineering Department. It was not a mass-produced kiosk like the K2 or K6 but was designed primarily for use by railway companies, private estates, and institutions such as universities or hospitals that required telephone kiosks on private land. The K4 was unique in that it aimed to combine multiple public services in one compact unit—serving not only as a telephone box but also housing a stamp vending machine and post box. As a result, the K4 was conceived as a multifunctional street fixture for convenience and economy. The K4 saw very limited service within the United Kingdom. A total of only about 50 units were ever produced, and almost all were installed in urban areas, typically outside post offices, railway stations, or civic centres. A few were also placed in industrial towns, such as Leeds and Newcastle. There are only a handful of surviving K4 kiosks today, with about 5 known examples remaining. Restored K4s can be seen at the Avoncroft Museum of Historic Buildings, and a few are in private ownership or public heritage displays. Some have been restored to partial working order, although the stamp and letter box functions are usually disabled or symbolic. Manufacture of the K4 was carried out by contractors specialising in cast iron fabrication, likely including firms like Carron Company in Scotland. Its designer was not a named architect but rather the in-house GPO team, building on the aesthetic of the K2, but with structural and functional modifications. The kiosk was made entirely of cast iron, with heavy bolted panels and a double-door compartment on one side to access the stamp machine and posting slot. The telephone compartment retained the six-pane door style similar to the K2. The kiosk was painted in the standard Post Office Red, with signage similar to that on other models: enameled TELEPHONE signs on each face beneath a flat or slightly domed roof. Interior electric lighting was included, as were small crown emblems embossed into the structure. It was slightly wider than a standard kiosk to accommodate its dual function, but ergonomically remained comfortable for one user. However, the addition of postal and vending compartments made maintenance more complex and prone to vandalism and misuse. Ventilation was adequate but limited. Because of its complexity and cost, the K4 was not adopted widely. It housed standard Button A/B payphones, later updated where units remained in service. Placement policy was guided by both the General Post Office and local councils or railway companies, depending on ownership. Politically, the K4 reflected an early attempt at infrastructure integration, but it was ultimately unsuccessful due to its maintenance burdens and lack of flexibility. Culturally, the K4 is a curiosity in the evolution of British street furniture. It never became a national icon like the K2 or K6 and is rarely seen in media. It does, however, hold appeal for enthusiasts and collectors. There was no significant public campaign to preserve K4s, but surviving examples have gained interest due to their rarity and multifunctional design. Some have been repurposed as micro-libraries or community information points, while others feature in art displays or museum exhibits. Documentation exists in GPO archives, and several heritage bodies such as Historic England have recorded their locations and status. The K4 remains a fascinating, if short-lived, experiment in the history of British public communication. |

Leave a comment