| Name | Kiosk No. KX300 |

| Date | 1996-present |

| Manufacturer | BT. The KX300 took inspiration from the Meclec Triangulaire and BTE/AW Anglian and reworked by DCA. |

| Usage | Accessible Public call box |

| Further notes |

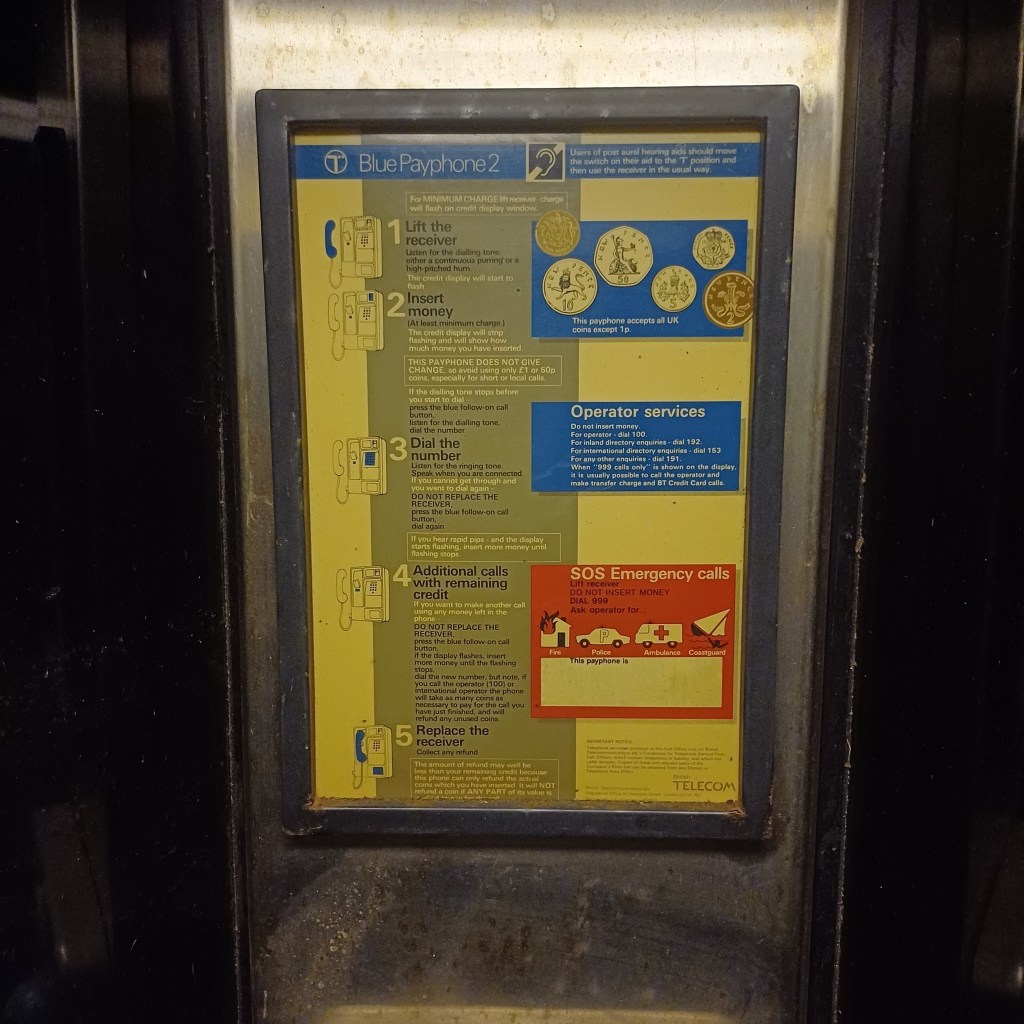

| Kiosk No. KX300 The KX300 telephone kiosk, introduced by British Telecom in the late 1990s, marked one of the final iterations in the long lineage of British public telephone boxes. Designed with a particular emphasis on accessibility and cost efficiency, the KX300 featured a triangular footprint and a doorless structure, setting it apart from all previous models. The design aimed to accommodate wheelchair users more effectively and to reduce maintenance by eliminating moving parts like doors, which were often prone to vandalism or wear. The KX300 was installed predominantly in urban and suburban environments across the United Kingdom, particularly in locations where space was constrained, or access requirements mandated barrier-free public facilities. Due to its extremely modern and functional appearance, the kiosk did not gain the same nostalgic or architectural status as earlier models and was rarely exported. Very few KX300s survive today, as most have been removed in response to the widespread decline in payphone usage and changing land-use needs. Some remain in situ in isolated areas or have been relocated to community spaces, local government facilities, or preservation trusts. Manufacturing was handled by specialist contractors commissioned by British Telecom. The KX300 was constructed from powder-coated steel, aluminium framing, and toughened polycarbonate panels or open steel mesh walls for visibility and ventilation. The structure had a lightweight, modular design for ease of installation and servicing. The standard colour scheme was typically metallic grey or steel blue, consistent with BT’s late 1990s branding. The kiosk featured a top-mounted illuminated BT logo for visibility at night, and lighting was integrated via low-energy internal fixtures. Ergonomically, the KX300 was notable for its open, triangular layout, designed to allow a wheelchair to roll directly into position beside the payphone unit. It had no door, ensuring unimpeded access and reducing the risk of entrapment or vandalism. The internal payphone was mounted at a suitable height for seated or standing users. Ventilation was excellent due to the open structure, though this also meant reduced privacy and exposure to noise and weather—common criticisms of the design. The payphones fitted were modern push-button digital models, compatible with coin use, phonecards, and in some cases, early chip-and-pin payment options. Their internal modularity made them relatively easy to maintain or upgrade. Location placement was determined by British Telecom in collaboration with local authorities, with an emphasis on public buildings, hospitals, civic centres, and shopping zones where accessibility was critical. The political context of the KX300’s introduction reflected increasing pressure on public institutions to comply with the Disability Discrimination Act (1995) and later accessibility legislation, making the kiosk both a telecommunications and a public service infrastructure response. Documentation of the KX300 exists within British Telecom’s engineering archives, GPO planning records, and local council planning files. Because the kiosk had a short service life and was often removed quietly, it is less frequently represented in heritage databases like Historic England. Internationally, the KX300 had virtually no export footprint, and there are few, if any, replicas abroad. It remains largely unknown outside the UK and is rarely reproduced for tourist or historical purposes. Restoration is uncommon due to the utilitarian nature of the design. Where it has occurred, it involves repainting and reinstalling signage, but there are no enamel parts, and original components are generally functional rather than collectible. The KX300 thus represents the final phase of Britain’s public telephone infrastructure—designed not as a cultural object, but as a service-focused response to accessibility legislation in a mobile-driven age. |

| Below- interesting example with a door. |

Leave a comment